I have been researching my family’s history for over thirty years, but it wasn’t until two weeks ago that I discovered a family history connection to Asheville. My maiden name is Gwyn, and my earliest known direct paternal ancestor was a man named Melon Gwyn. He was born in about 1850 in Surry County, NC, a likely slave of the Gwyn family. The earliest record I have found of him was from his marriage in 1873 to Martha Headspeth, whose parents Richard Headspeth and Lucy Fowler were both free as early as 1840. Melon’s mother’s name was listed as Sela or Cila Gwyn, and his father’s name was left blank, which in my experience with other family members from this period often means that the father was a white man known to the family, but left unidentified publicly.

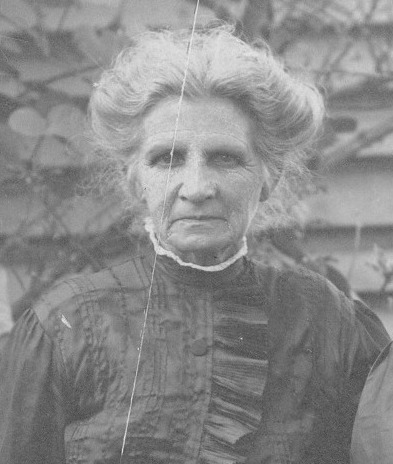

Many people assume that the last name their ancestor carries is the name of their last slave owner. This is actually not quite correct. I don’t have any large statistical studies about the percentages, but I have seen in my own family that often an earlier slave owner’s name was chosen. (For more on this subject, please read historian Melvin Collier’s blog post Roots Revealed) Another assumption many families make when researching their African American family history, especially about their very light skinned or mulato ancestors, is that the slave owner is the assumed father. The sad truth is that slave women were powerless against nearly any white man in their presence. Although there are certainly many slave owners who fathered children with their slaves, in some cases the father is another relative of the slaveowner, an overseer, a neighbor, or another slave. For example, the oral history on one of my grandmother’s ancestors was that a Sanders slave owner was the father of my great great great grandmother, Phoebe Sanders. The paper records have revealed that her father was another slave by the name of Richard Porter, her mother was a slave named Esther Austin, and the Phoebe was owned at different times by families named Sanders, Trigg and Kincannon and had been known in the community through her connection with each of them. A photo of Phoebe’s half sister Rachel, another of Richard Porter’s daughters shows her to be a very light skinned black woman, and both of her parents were slaves as well. Her parents were very likely of mixed race, and I hope that someday DNA will give me more answers about that. (Side note: Oral history also said that we had Native American roots on several lines on my father’s side of the family. The DNA answer is NO!)

Rachel Porter Songer, born into slavery, the daughter of slaves. She was the half sister of my GGG Grandmother, Phoebe Porter Sales.

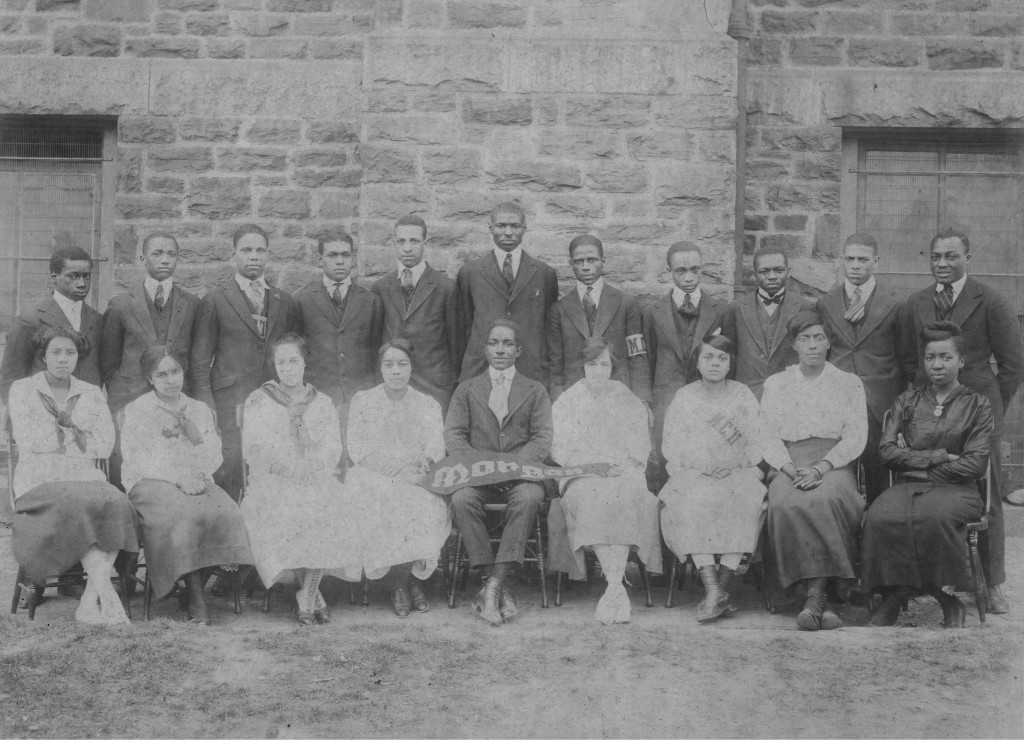

Back to Melon… I also had made assumptions about his slave holding family and his parents. Although I do not have a photo of Melon, I have several photos of Melon’s son James, (my great grandfather.) I believe it is very likely that Melon’s father was a white man. This is a photo of two of Melon’s sons, James and his unidentified brother.

I long suspected that Melon’s father might have been James Gwyn, part of a large family of Gwyns in Virginia, North Carolina & Tennessee who owned hundreds of slaves between them. Research into slaveholder James Gwyn’s family revealed names that were also part of my own family: James Gwyn has brothers named Hugh and Richard, and a son named Walter. Melon Gwyn named his eldest son Hugh Richard, and two other sons Walter and James. I was able to read James Gwyn’s plantation diary and many family papers of his because they were donated to the UNC Chapel Hill library. He permitted his slaves to be baptized and married, and while he wrote about them in a very paternalistic way, nothing I read gave me a notion about him fathering children among them. Of course, I can’t imagine that is something a slave owner would write about… In the end, however, DNA testing might have answered that question for me. None of our DNA matches has the name Gwyn in their family trees, but several have the names Martin and Dowell, two families living nearby and very closely associated with James Gwyn’s family.

My new find in Asheville, however, has given me more reasons to suspect a very close relationship between James Gwyn’s family and Melon’s family. I was never able to find reference to Melon or his mother Sela in any of James Gwyn’s family papers or in any other written record until his marriage in 1873 in Surry County, NC. In 1880, Melon lived with his wife Martha and their four sons in Watauga Township, NC. He worked as a farmer and both he and his wife were able to read and write. In 1900, he and Mattie are listed with their ten children in Cranberry, Mitchell Co., NC. He worked as a day laborer and owned his home free (no mortgage payment). In 1910, Martha is listed as a widow and she and her children were living in Pittsburgh, PA. I recently learned that two of her sons died that year, Edward on April 10th and Charlie less than two weeks later on the day of the census, April 26, 1910, both of pneumonia. Melon’s history after 1900 and the date of his death were a mystery to me.

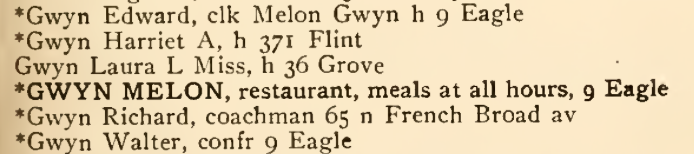

Then, two weeks ago, while searching Ancestry.com, a search result came up for Melon Gwyn in the 1904 Asheville City Directory. After over twenty years, the shock of finding him here in Asheville still hasn’t worn off!

Also listed on the page were three of his sons: Edward, Richard and Walter. A few days after making this discovery, I was able to find two newspaper articles referencing Melon.

A year later at the bottom of an article about Blowing Rock’s Watauga Hotel there was this:

I was surprised that less than a year after being arrested for breaking and entering, a black man was recognized in the newspaper and hired for a job with some prestige. I found myself wondering if he had some kind of help or community connection. I looked more closely at another Gwyn whose name I kept coming across here in Asheville, Walter B. Gwyn. Walter’s papers from 1891 to 1897 have been donated to the Ramsey Library and many are online and transcribed. From Ramsey Library:

Walter B. Gwyn, a native North Carolinian, was raised in Wilkes County. Green Hill Plantation, the family home, was later occupied by Walter’s brother, James Gwyn and family, his sister, Mary and his mother. A lawyer by trade, Gwyn worked most of his career in Asheville…

Walter B. Gwyn was the son of the slaveholder James Gwyn. Melon arrived here in Asheville shortly after Walter came here. I learned from Walter Gwyn’s papers that he was also in Blowing Rock at the time the Melon was hired at the restaurant. Of course, these might be just coincidences, but at this point I’m having trouble believing in coincidences.

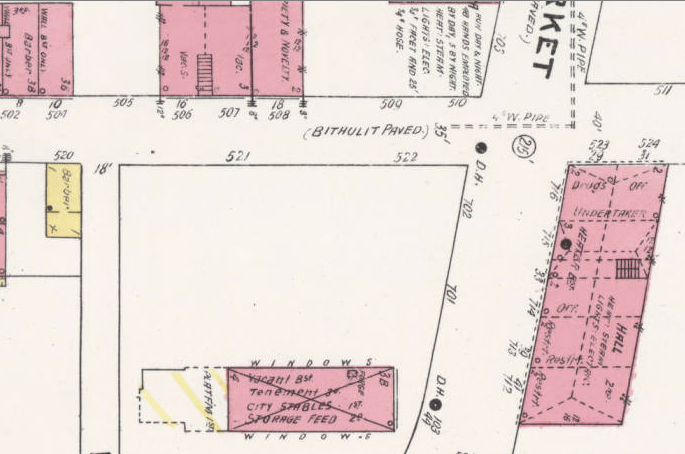

A correction in the back of the city directory says that 9 Eagle St. should be listed as 10 Eagle Street. A detail of the 1907 Sanborn Fire map shows 10 Eagle second from the top left (YMI is the building in the bottom right.

8 Eagle St was a barber shop, and today is the location for Smooth’s DO Drop In barbershop. Below is the location as it appeared in the 1950’s. Melon’s restaurant would have been to the right of the Billiards sign.

Image L382-DS from Pack Library’s North Carolina Collection

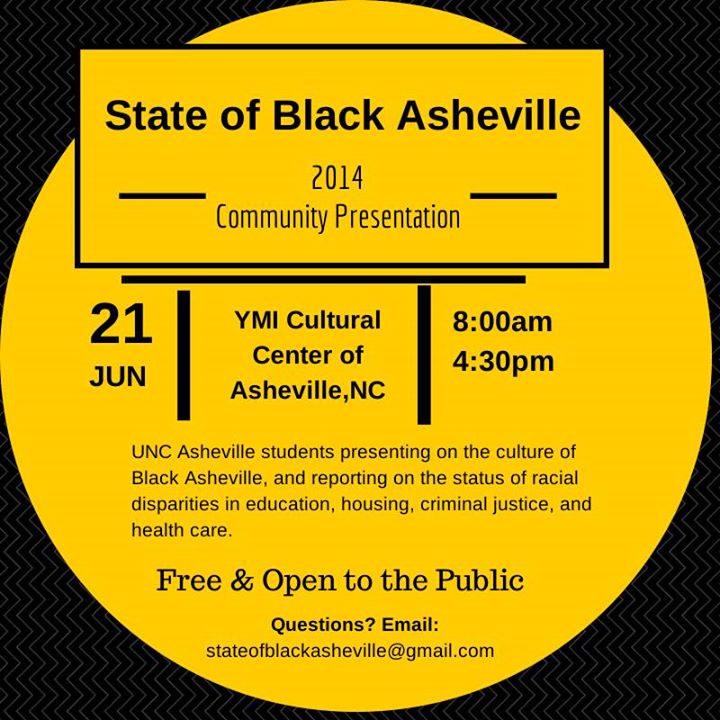

This discovery has given me a new sense of connection to Asheville. I think of my work in studying the history of the Eagle & Market Street business district, and in helping to promote Asheville’s locally owned black businesses and I have to think Melon Gwyn would have been proud and truly amazed at the path that led me to this place. I’m so grateful to call Asheville home, and now part of me feels that all along Asheville was calling me home.